In TEKKEN 8, it takes roughly 3 hours to get through the story mode, with about half of that being cutscenes. Enormous amounts of money were invested into producing it—high quality animations, cinematic direction and lighting, unique control schemes. It amounts moreso to watching a movie than playing a game.

This is the feeling the player gets after those ~3 hours: they just watched a movie. They come away from those 3 hours not having learnt anything about the game itself. If they have learnt anything, it’s that you play the game by randomly mashing buttons. After watching this movie, if they wanted to play TEKKEN with their friends, or play ranked online, they would at best be in the same place they were 3 hours prior.

This is insane. It’s an indescribable failure. After having 3 hours of the player’s attention, the game still needs to give them a tutorial before they can actually play the game. Worse still, it hasn’t convinced them in the slightest to want to.

In this article, I will describe what a story mode designed to use those 3 hours of attention properly would look like. Then, I will explain why this was not done in TEKKEN 8, and why this is a significant and unnecessary reason the genre is so niche.

How it should work

The surface promise of a fighting game’s story mode should be this: you learn how to play the game, and if you do we’ll show you an epic story. This is already the promise of character action games like Bayonetta, Devil May Cry, and Ninja Gaiden. However, there are two key differences: those games do it better, and those games don’t have the same endgame to promise after you’ve finished.

With a fighting game, the endgame of the story mode is the versus mode. This is a tantalizing thing to promise! “Finish the story mode, and you’ll be ready to play the real game!” There is a massive audience of players who would enjoy fighting games if they could get over that initial hurdle of actually trying them out.

Now, I can already hear the objection. “So, what, you just want the story to be a tutorial? But players hate tutorials!” Yes! They do! But have you asked why?

Players hate tutorials because learning new things is frustrating and they aren’t convinced it’s worth the effort. This is why the promise of “you’ll be able to play the game after” fails when it’s the only promise. How do I know I want to play the game?

When viewed this way, the solution, and what’s being wasted, is obvious: the story is the hook. It will get people to actually play the tutorial. Players will tolerate some frustration if there’s an epic story pushing them along. Then, once they’ve had that push to get them over the first hurdle, they will find themselves empowered to enjoy the deeper game of the versus mode. Suddenly, a short-tail customer is converted into a long-tail one.

TEKKEN 8: The Dark Awakens – cthor.me rewrite

I’ll use TEKKEN 8’s story as the basis for an example of what it should’ve been. I will be rewriting it in parts where necessary to exclude things that don’t do one of two things: hook the player in, or actively teach the game.

What will we learn?

Before getting started, we should identify what the player should know after finishing the story mode. This will inform the narrative beats.

- How to dash

- How to run

- How to attack

- How to do strings

- Difference between high and mid attacks

- How to crouch

- How to block

- How to block punish

- How to sidestep

- How to whiff punish

- How to backdash

- How to powercrush

- How heat works

- How to throw

- How to break throws

- How attack speed matters

- How to do mixups

Who are we playing as?

One of the worst parts of TEKKEN 8’s (as well as TEKKEN 7’s) story mode is that you have to play as multiple different characters, constantly swapping between them each chapter, often with full access to their entire movelists (although in some cases with some modification).

What if I don’t want to play as Alisa, or Leo, or Victor, or Reina?

If we want the player to actually learn what they’re doing, rather than just randomly mash random buttons until they find the ones with the longest strings and the biggest hitboxes, we need them to pick and stay with one single character. We can’t expect to present players with challenges while we’re constantly shifting underneath their feet the basic controls.

This means one of two things: either they play as Jin, or they’re given a choice of who to play.

Either one of these works. The narrative direction will be different depending on which we go for, but we have to pick one.

I’m going to go with the latter, primarily because it’s less restricting. If we’re forced to only play as Jin, then we can only play out scenes where he is actually present. (It’s possible the story to be told really does focus a lot on the protagonist, and in that case them being the playable character makes more sense.)

This is probably the reason for the constant character swapping—Jin just isn’t there for a lot of scenes. There’s no character who’d be there for every scene. So if we’re treating it as a movie and not a game, then we have to swap the playable character all the time. Good thing it isn’t a movie. Video game logic dictates that, yes, Bryan Fury can totally be the good guy helping Jin if he’s the playable character. Hell, we can have player character Kazuya fighting antagonist Kazuya.

Chapter 1

Scene: Kazuya is levelling an entire city, about to make his declaration of war against humanity. Jin steps up to challenge him. Just as their duel is about to start, the scene cuts. You are not ready to fight yet.

Scene: Jin is at Yakushima, being trained by his mother, Jun. She starts with the basics. In this scene, we have a special player model for child-aged Jin. His moveset is limited to movement and a single jab. Jun instructs him in a firm but motherly tone.

First battle: Wooden training dummies spawn far away from child Jin. The player must move forwards and strike them before time runs out. Walking forwards is not fast enough, he must dash or run to finish in time.

Second battle: Larger wooden training dummies spawn. These have more health. Jin can now perform 1,2 and is instructed by Jun to perform a string of attacks to win. Single jab doesn’t do enough dps, so he must use the string to finish in time.

Third battle: Even larger wooden training dummies spawn. These have even more health. Jin can now perform 1,2,4 and is instructed as such by Jun. 1,2 doesn’t do enough dps, so he must use the full string to finish in time. The dummies don’t have normal hitstun animations and don’t get knocked down by 1,2,4.

Fourth battle: Smaller wooden training dummies spawn. These have less health, but are too low to the ground, so highs whiff. Jin can now perform df+1 and is instructed as such by Jun after he whiffs a jab.

Boss battle: Mokujin-shaped training dummies spawn. These perform a wound up, high counter-attack whenever Jin hits them with 1,2,4. 1,2 still doesn’t do enough dps, so he must use the full string to finish in time. If he gets hit by the high, it knocks him far away, wasting precious time. If Jin gets hit twice, his health hits zero and he loses the battle. If he blocks the high, it has a lot of blockstun and pushback, also wasting precious time. Jun will instruct Jin to be patient and dodge the attack by crouching. The only possible way to kill the boss in time is doing 1,2,4 for dps and then ducking the high.

Scene: Jun yaps a bit about fighting for peace or something.

Chapter 2

Player is presented with a character select screen. Jin is the default option, and if he’s chosen you get a clone character instead. We do this for Jin, but not any other character, because it’d be a bit confusing if there were both protagonist Jin and player character Jin. Also, there are a few scenes in the story where we play as protagonist Jin, so we kind of need player character Jin to clearly be distinct. For every other character, we’re okay with video game logic, so e.g. no issue having a Kazuya mirror if you pick Kazuya.

Scene: Jin brawls with Kazuya in the streets. They play out a TAS-style choreographed sequence with a lot of visual spectacle. The idea is to make them look like they’re far beyond anyone else’s skill level. Eventually Kazuya overcomes Jin and tosses him across the street. As he lunges forward for the finishing blow, you step in and block it.

Boss battle: Kazuya in the rubble of the city streets. Jin is off to the side, injured, and encourages and coaches you when necessary. Kazuya uses a wide array of powerful, multi-hit strings that are all mids enhanced with homing and armor properties. If you attempt to brawl with him, you’ll be easily overwhelmed. Kazuya taunts every time he counter hits you.

There is a timer, and if it runs out, Kazuya does some busted ass laser move and kills you. Try again.

The key to this battle is you must block Kazuya’s attacks and then punish them. When this is done, Kazuya comments in a way that comes across as mildly dazed. He’ll stop attacking or blocking for a few seconds. After a while of being beat up, or after taking enough damage, he’ll use ancient power and resume his assault and taunting.

When Kazuya’s health reaches 25%, the battle ends. A short sequence plays out before Kazuya rushes forward and chokeslams you into the rubble. From player character POV, vision blurring, you look on helplessly as Kazuya approaches Jin, before fading to black.

Scene: Kazuya flies above the ruins of the city and declares war on humanity. He announces the next King of Iron Fist tournament and boasts that even the strongest of humanity will be no match for him. The various characters view the broadcast from wherever they happen to be, e.g. Victor and Raven from their submarine.

Chapter 3

You’re in the Asia A block qualifier for The King of Iron Fist Tournament. Reina is also in A block. Jin is in B block, which is held in the same place on the same day.

Scene: Hallway, Jin walks past you and bumps into Reina. She does the whole pretending to be a random girl routine. Jin keeps walking. She drops the bubbly act in front of you. “Who are you?” Then she says something like she’ll see you in the tournament if you’re worth talking to.

First battle: Hwoarang in the Arena. There is a color commentator who coaches you, but the lines are as if he’s talking to the crowd. Hwoarang uses a wide variety of strings which are all plus on block armored mids. There are no gaps in his pressure where you can successfully mash your way out. He is always plus and dealing chip damage.

The key to this battle is that you have to sidestep his pressure. All of his attack sequences have at least one gap where you can sidestep. If this is done, his attacks have a special whiff animation where he almost trips over, similar to Asuka f,F+1. If you punish him during this whiff animation, he’ll stop attacking or blocking for a few seconds. After a while of being beat up, he’ll block everything for a few seconds and then restart his pressure.

Scene: Jin faces Lee in the semifinal for B block. Lee partially awakens the Devil Gene mid fight and eventually loses. Reina observes from the crowd with curiosity.

Scene: Reina faces you in the finals for A block. She sees Jin in the crowd and puts on her bubbly facade, trying to be friendly to you.

Boss battle: Reina in the Arena. Reina fights differently to every other boss so far. She spends a lot of time not attacking, instead moving around smoothly between her stances. If you try and do any mixups, she blocks all of them, punishing them if possible. She also breaks any throws. When she does choose to attack, all of her attack sequences start with armored mids, so beating her by mashing is out of the question.

The battle has two parts, both are timed. If the timer runs out, she kills you instantly with some bullshit.

In the first part, we have a repeat of what was learnt vs Kazuya. Her attack sequences all end in unsafe on block mids. Block and punish for the win.

When you get her health to 0%, she performs one of Heihachi’s moves. Jin, watching the battle, recognizes these techniques and starts suspecting she isn’t just some random girl.

In the second part of the fight, her attack sequences are more explosive. The second to last hit is plus on block and has a lot of pushback. The last attack in the sequence covers the remaining space, so anything you throw out loses. The counterplay is that you have to backdash in between this sequence to make the last hit whiff. Much like against Hwoarang, when she whiffs this move she’ll almost trip over with a long whiff animation. After punishing, you get to wail on her for a bit.

Scene: Jin confronts Reina in the hallway about her Mishima style techniques. She acts dumb.

Chapter 4

Scene: Final tournament plays out.

It’d be cool to have all the fights between the non-player characters play out TAS style with in-game combat, but it may be difficult to choreograph that many cool looking fights.

If this isn’t possible, they should just happen off screen. Forcing us to play out all these matches is one of the worst parts of the original story, because it’s obvious none of the fighters involved matter to the plot. (It’s obvious that Jin will win.)

I’ll stop here. You get the idea: Each battle presents a genuine challenge to the player that must be overcome. In doing so they learn something about the core game mechanics, preparing them for every other game mode. The remaining chapters would continue introducing concepts like heat, mixups, throws, and frame data. The final bosses would combine these ideas to further up the ante and demonstrate how it all comes together.

Cut scene: TEKKEN Force

Scene: Rebel army regroup in the hangar and discuss their plans to battle G-Corp.

Scene: Huge battle between rebel army and G-Corp forces.

This entire section of the story only exists to shoehorn in the beat-em-up mode because fans love TEKKEN Force. Narratively it makes no sense, and there’s no good way to use this gameplay to teach the player anything relevant to the versus mode because it’s a fundamentally different genre.

There isn’t anything inherently wrong with this mode existing. Beat-em-ups are a classic and beloved arcade genre. A skilled designer familiar with it could very well make an excellent TEKKEN Force mode.

However, this should be a separate game mode and story. The goal of our main TEKKEN story mode is to supplement and onboard the versus mode. A sudden genre shift in the middle is completely contrary to this goal and necessarily leads to dumbing down both modes for the player to be able to handle the whiplash.

Why doesn’t this happen?

Fighting game developers currently split their target market into two caricatures:

- Casual players. Glue-eating morons who are not capable of and actively resist learning anything.

- Competitive players. Sophisticated critics who can use their brains and require advanced features.

The general consensus is that casual outnumbers competitive by several orders of magnitude. However, this presumed split is an illusion. Neither of these customers are real. Falling for this illusion leads to fundamentally bad game design and is a major reason fighting games are so niche. If this illusion were broken, fighting games could be at least as popular as Chess, which has (depending on how you count it) roughly 10–100x more active players than all fighting games combined.

The story mode is designed for the first customer. Thus, it is absolutely imperative that they not be challenged at all by it. There should be no possible road block that would require them to exercise brain function in order to experience the rush of colorful flashing lights appearing on their screen.

The versus mode is designed for both customers. Thus, there are a number of design decisions in it that are absurd and contradictory. There is an online mode with rollback, but you can’t fix the delay frames. There is a WiFi indicator, but you can’t filter by it and it’s trivially spoofable. (If they thought you really cared about this, you’d be able to filter by jitter.) There is a ranked system, but it’s intentionally exploitable. There is a matchmaking system, but it fails to match you with appropriate opponents. There is a community hub, but there is no effort to moderate it or provide matchmaking. The best player wins, but there are robbery mechanics and slow, forced mixups to flatten the skill curve.

Is there any surprise that this design largely does not appeal to people? That the genre is niche? The cynicism oozes from its every pore. No matter who you are, it feels like the game hates you, because it does. It does not respect you. It does not respect your time. It thinks you’re a child who needs flashing lights on the screen at all times to keep your attention and doesn’t dare challenge you. It thinks you deserve to be clowned on by someone rolling their face on the controller because, “Hey, they paid $80 too.”

Developers in other genres don’t view their target market this way, and thus those games are not designed under this illusion. Even gacha games don’t have this much contempt for their players. As predatory as they are, they still take the core gameplay loop seriously. Consequently, people actually play them.

Every boneheaded game design choice fighting games have made in the last 15 years is downstream of this illusion. Removed motion inputs, reduced execution, combo breakers, generous input buffers, button binds, shortcuts, shallow and repetitive mechanics, meter creep, simplified mixups and oki, excessive timestops and cinematics. None of these have attracted a larger audience because, aside from actively making the game worse, they don’t address the root cause. They don’t make onboarding any easier.

The only game design choices that have remotely helped with onboarding are things like KoF XV autocombos and SF6 modern controls. Notably, both of these are suboptimal. They’re merely stepping stones to get people playing the game first. They don’t remove the depth available.

Here’s a better way of viewing the target market:

- Inexperienced players. People who have never played fighting games before, but are aesthetically interested in them.

- Uninitiated players. People who have played other fighting games before. They know they like fighting games and want to get into this one, and they don’t want to suffer through a long, boring story mode to start playing it.

- Initiated players. People who can open up the game and have fun in one of the various long-tail modes (photo, customization, versus, ranked, lobby, etc.).

The ideal story mode would turn inexperienced players into initiated ones. The ideal training mode would quickly turn uninitiated players into initiated ones. Currently, most training modes succeed somewhat at their job, but most story modes fail at theirs. More precisely, they don’t even try.

The difference in skill level amongst initiated players is not so important. Low-skill and high-skill players have the same interests: that the game is fun and deep, and that they are rewarded for their training.

There is a massive space of game improvements one can make that appeals to one without sacrificing the other. Rarely is there a true need to make a tradeoff between them. In almost all cases where the appearance of such a tradeoff exists, it’s the fault of bad design, and not anything inherent to the competing interests of these players.

Again, I can hear the objection. “But what about all these scrubs who just want free wins? They’re everywhere! Devs need to appeal to these unwashed masses.” This is another illusion. These people aren’t real—or rather, that isn’t how they think.

Yes, it’s true that there are people who want all the reward with none of the work. One need only look in the mirror to see that. But everyone also knows that in a competitive PvP game, it takes two to tango. For every winner, there’s a loser. Most people can accept this: that if they want to win, they must work for it, and the stronger their opponents are, the harder they must work.

There are a small minority of people who are not mature enough to accept this. These are people who happily use cheats in PvP games if they can get away with it. They comprise roughly 5-10% of people, and they are toxic to any online gaming environment. The game design, if it considers these people at all, should be actively hostile towards them.

However, the overwhelming majority of scrubby behavior is not a result of any flaw in the player but a flaw in the game. What does the story mode teach you? Mash random buttons until the enemy health drops to zero. What does the ranked system teach you? Plugging and cherry picking are rewarded. What options are there after a match? Rematch, or find a new opponent. No button to go to the replay. What does the training mode actively teach you? Nothing.

Is there any point at all where the game actively teaches and rewards you for things like… trigger warning… blocking?? Quelle surprise that players aren’t doing it.

World Tour

Lest you think Bandai Namco are uniquely myopic, Street Fighter 6’s World Tour mode is arguably worse. Not only does it take longer to finish (closer to 10 hours for an average playthrough), it does demand the player learn some things. It’s just that what it demands they learn is totally irrelevant to the rest of the game: how to navigate the World Tour environment and menus; the layout of and key locations on the various maps; how to farm level ups; how to unlock certain avatar gear, outfits, fighting styles, Master Actions, etc; what the hell a Master Action even is.

(There are some very limited times where World Tour mode actively forces you to learn things relevant to the versus mode, but this is such a small portion of the total play time that it’s hardly worth mentioning.)

As a game in and of itself, World Tour is boring and lifeless. People only play it to unlock things for other modes. It’s almost insulting how bad it is. Barely any of it is even voice acted. Even if one evaluates it as a gacha game it falls flat with its sterile environment and lack of sex appeal. At least TEKKEN 8 has the decency to be short and densely packed with expensive production.

Street Fighter 6 is more successful than TEKKEN 8 because the rest of the game is more accessible and better designed for creating long-tail customers. But that’s a whole other article.

I focus on TEKKEN 8 because its story mode is closer to what would be ideal, so it’s easier to use a reference point, but also because I’m more familiar with it.

More Chess comparisons

Chess makes a good point of comparison because it shares many key elements with fighting games: they’re competitive 1v1 games, played sitting down, usually with games lasting 5–10 minutes. (The latter is a more modern phenomenon, but overwhelmingly this is people’s preferred time control online.) If you lose, it’s your fault. There’s no team to blame.

People spend hours outside of the game learning to get better at it. Books are written about it. Courses are taught. People get paid to teach it. A computer can tell you in an instant what mistakes you made.

Whatever the total addressable market is for fighting games, it has to at least be as big as Chess is. (It should be much larger, frankly, because video games have the potential to be so much richer and deeper than board games, and they should have a much easier time appealing to new players, but that’s a whole other article.) Fighting games cannot be so small-minded as to think their present niche market is all they can hope for. If they understand this, they can stop copying each others’ failures, and start growing the genre as a whole.

There are a number of things fighting games developers can learn from Chess websites, all of which are catered entirely towards initiated players. (They largely piggyback on shared culture converting people from inexperienced and uninitiated into initiated, although they do usually have a tutorial as well.) Because they can’t change the game itself, they provide a good reference for the kinds of things fighting games could do to improve the experience for initiated players without changing the game itself.

I want to emphasize that all of these things could easily exist already, but they don’t because of the aforementioned illusory view of the target market. Fighting game developers don’t add these features because they think you don’t want them.

Learn from your mistakes

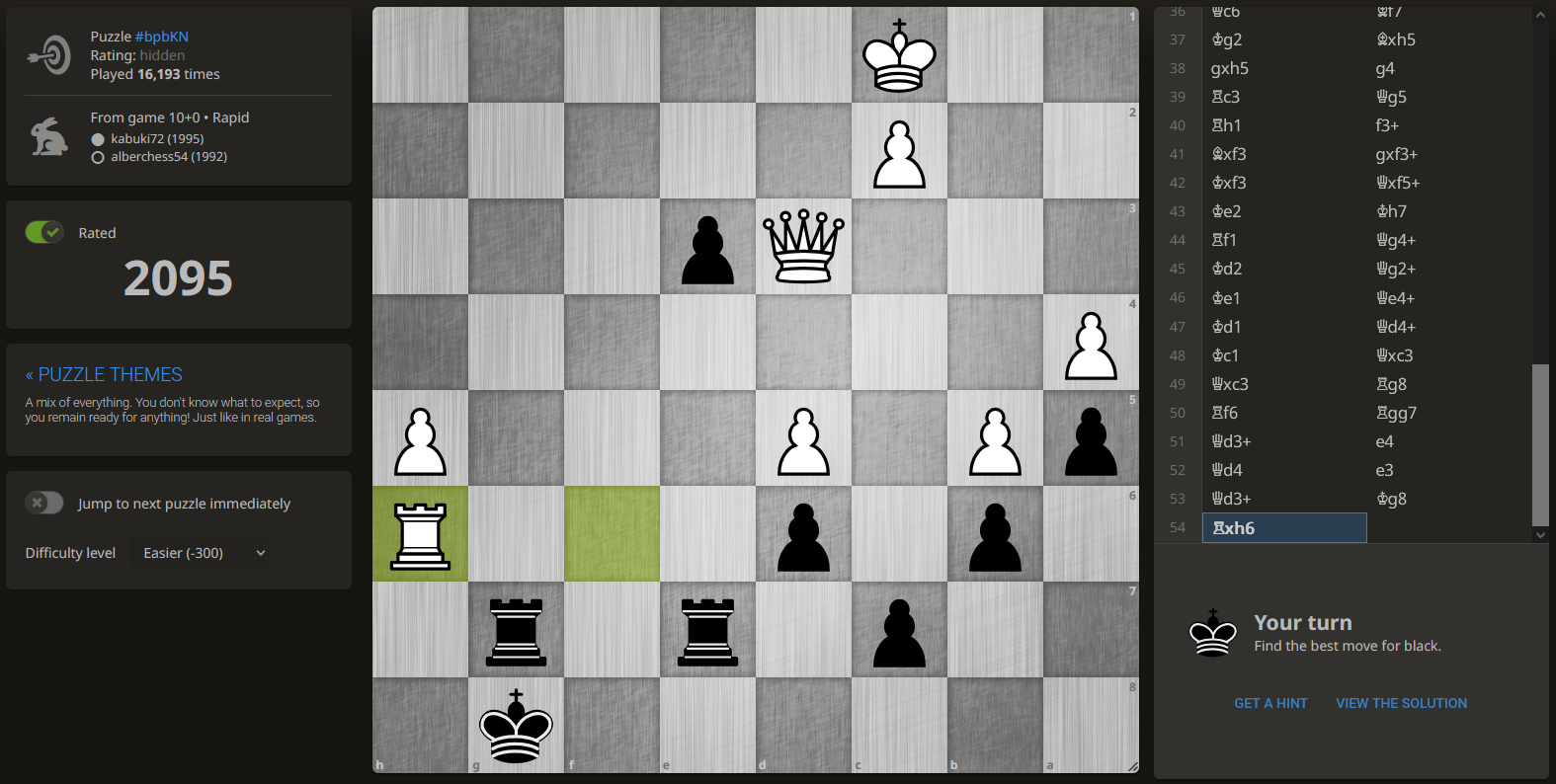

When I finish a game on lichess, below ⟨New opponent⟩ there’s an ⟨Analysis board⟩. Click that and there’s a ⟨Request computer analysis⟩. Click that and then shortly there’s a ⟨Learn from your mistakes⟩, which shows:

It takes me less than a second to notice that while Rh3 saves the hanging rook, it leaves the f2 pawn catastrophically unprotected. I try Rf4 and it tells me this is much better, but says there is another, even better move as well. I try Rxe4 and it says this is best. I think I can see why—I’m up a piece, so losing the exchange is fine, and black’s entire centre crumbles after 28… Rxe4 29. Rxc5—but I would never see Rxe4 on my own. I would surely see Rf4. So there is something else important that this screen shows me: I was in time trouble.

In under a minute, the game’s tools have improved my tactical skills and made me aware that my time management needs work. I didn’t have to go out of my way to set up training mode, or find the replay, or identify the points in the replay where I messed up. The game did all of those tedious things for me. After this very brief interlude, I can then go back and play another game.

What would the equivalent flow look like in a fighting game? I should have a button right below rematch saying ⟨Learn from your mistakes⟩. It should take me right away to the points in the replay where there are e.g. punishable moves, duckable strings, dropped combos, etc. Why is this not a thing?

Puzzles

Puzzles take many forms, but the basic idea looks like this:

You enter this game mode and it presents you with some challenge that has a closed solution. The challenge is tailored to your skill level so that you don’t get bored by something too easy or frustrated by something too hard. It does this by giving each puzzle a rating, which goes up or down much like any other rating would, where passing the challenge is like a win, and failing is like a loss (vs the puzzle).

Because they need closed solutions, a lot of things can’t be taught through puzzles. They’re best for teaching tactics, which is only one skill of many. That doesn’t mean they aren’t useful. Just that they have a clear limitation as a teaching tool.

Some people find puzzles more fun than actually playing and spend most or all of their time just doing puzzles. This is where the variations like Puzzle Streak, Puzzle Storm, and Puzzle Racer come in. Puzzles can effectively be another long-tail game mode if they are fleshed out well-enough.

The applications to fighting games should be obvious: defense training and combo trials. While, yes, you can do defense training right now in training mode, the amount of time you have to spend setting it up makes this a non-starter. Just as nobody goes to the Chess board editor to do puzzles, barely anyone uses training mode to practice defense. There are 99th percentile TEKKEN 8 players who don’t use it.

There should be an entire library of defensive routines and combo trials that the game can throw at players, all of it tailored to skill level, testing a wide range of skills from the humble block punishment to things like reaction checks, string punishment, fuzzy guards, and option selects. And these challenges should be thrown at you like a rhythm game: extremely fast, lots of feedback on performance, stat screens, scoring systems, etc.

Punishment Training and Replay Takeover are a nascent form of this concept, but very far from sufficient. Challenges tailored to the player’s skill level are table stakes here.

Imagine if you could pop open the game and immediately jump into combo trial mode. It gives you a specific save state on a specific map vs a specific character and you have to land this specific combo, first try. Succeed, and your combo trial rating goes up, and then it gives you a harder combo. Fail, and your rating goes down, and it gives you an easier combo instead. The potential depth for this game mode alone would be insane. Of course the combo trials would be created by players as well. Think of how many players would love spending hours making these combo trials. (This might not be the ideal form of a combo trial mode, but you get the idea.) We’ve just created two long-tail game modes for the price of one!